On Saturday, I slept late. My whole body ached, right through; my sleep disturbed by a Rubenesque German with sleep apnoea snoring three bunks over, and my throat still constricted and tight. I didn’t know if it was the sleep deficit or something deeper, but I could feel a kind of creeping anxiety heading for me, leaving me with the sense that I was only a few steps from teetering on a tear-slicked clifftop. Weeks on, as I write this, I barely remember my third day in Tokyo at all and my photo archive just shows a shot of a fortune I’d got at Toshugu, with a little golden tortoise. I think I must have spent the day catching up on my writing, eating onigiri, and sleeping.

But Sunday came, along with the determination to enjoy it. Today I would take the train out to the Folk Art Museum, the Mingeikan (民藝館) and treat myself to a gentle afternoon of staring at pots. Located out in the quiet suburb of Komaba, the Mingeikan was established in 1936 by Yanagi Soetsu, who’s kind of a big deal in the world of Japanese pottery. I must confess that despite a 3 year degree in ceramics, I only learnt of his work and its importance when by complete blind chance I transcribed an interview with a contemporary Japanese potter a month or so ago.

If you need an afternoon away from huge crowds, noisy adverts, and flashing lights, this is a grand choice. The collection features artefacts from across Japan in a range of materials, with a permanent section and changing exhibitions. I think. To be honest, it was hard to tell what was going on, because not only were all the signs in Japanese, they were in handwritten Japanese in red on a black background, which I had about as much chance of reading as The Winds of Winter. Still, from a purely visual experience, the Mingeikan is worth a look. The building itself is very beautiful, with strong beams and clean lines. All visitors have to take off their shoes and shuffle around in communal slippers (how everyone in Japan doesn’t have athlete’s foot, I don’t know), which almost creates an institutional air. I half expected to see staff members in white coats restrain and sedate someone.

Here I finally cracked out my sketchbook, my hand partially and semi-reluctantly forced by the photography ban. The museum was fairly busy, but I was able to position myself in various nooks, eyes open to others peeking in at my periphery; ready to scuttle out of the way when needs be. Museum drawing can be a fraught affair. I was once literally elbowed aside in Death exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London when an older gentleman decided I had been sketching in front of a book of Grim Reaper lithographs for too long. I guess he felt he was running out of time to see who was coming for him.

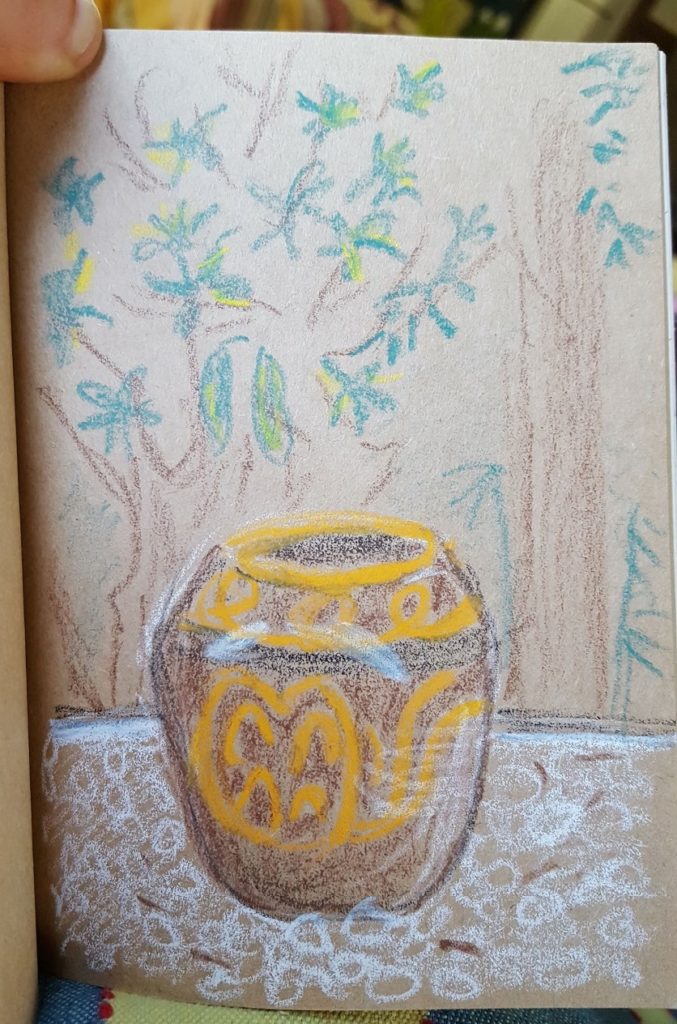

Up on the second floor I settled in on a long window seat overlooking a gravelled rooftop and began to draw one of the huge pots that occupied it. Despite my five years of ceramics education, I never got the hang of the wheel. It’s the kind of creature you have to work with every day to tame, until your muscle memory takes over and carries your hands through each of the barely perceptible motions that drags and shapes the clay from a soft wet lump into a vessel. I can just about make an ashtray. Anything larger than a water pitcher for the table amazes me, and it seems like I’m not alone in this. As I sat there a small girl rushed towards the window exclaiming “すごい!すごい!”Her mother bent down and whispered something, gesturing to the pot. “すごい!”, she said again excitedly, and again and again and again until suddenly she was so excited that she gave herself hiccups. It was like watching someone I’d locked deep inside myself and partially forgotten reintroduce themselves.

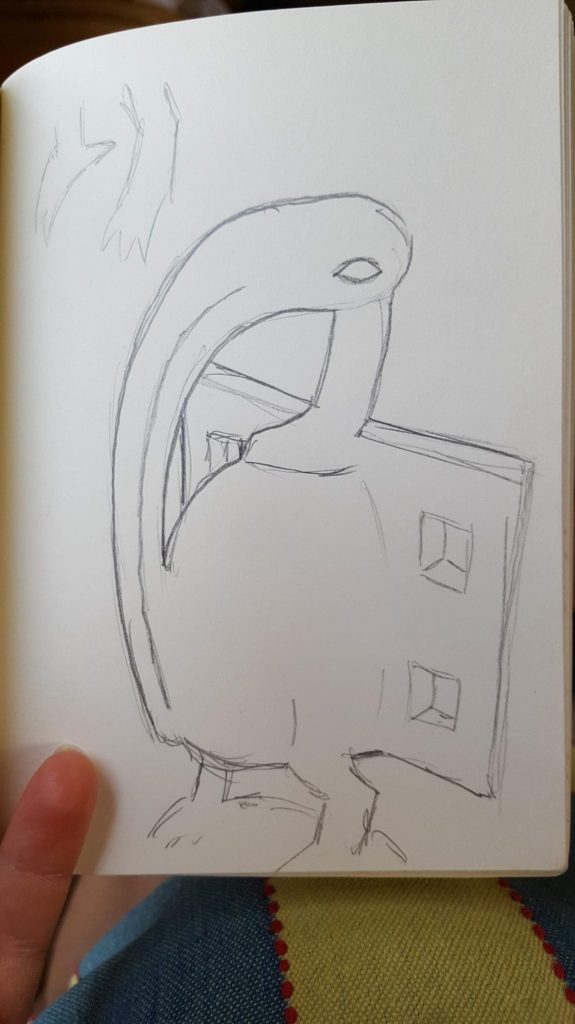

I retreated to the last room, trying not to giggle at the soft accompaniment of “hicc… hicc…” and began a sketch of a naïve wooden bird sculpture. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed the little girl stare at me, then turn to her mother to tug on her sleeve in request. A gallery attendant materialised to my left and began earnestly and joyfully forcing a pencil onto me. The Mingeikan has a policy of not allowing any ink, fountain pens, or watercolours, a request which is entirely reasonable for the preservation of work, and entirely frustrating when you’re faced with a collection of objects that beg to be put to page with a brush pen. Still, I’m a good girl and, resisting temptation, was using a mechanical pencil, but the word for any kind of pencil (えんぴつ = pencil, シャープペンシル = mechanical pencil) had completely escaped me and so it took lightly frantic clicking, scribbling, and waving to convince the attendant that I had read the rules. The interruption completely nuked my desire to continue the drawing.

On my way out, I noticed the little girl fervently drawing in front of a large tapestry; black pen on lined paper from her mother’s notebook. I liked this rebel even more. Please, whoever you are, keep that part of you I saw, and I’ll try and keep my own inner child who gets excited at big pots and breaks rules that get in the way of art.

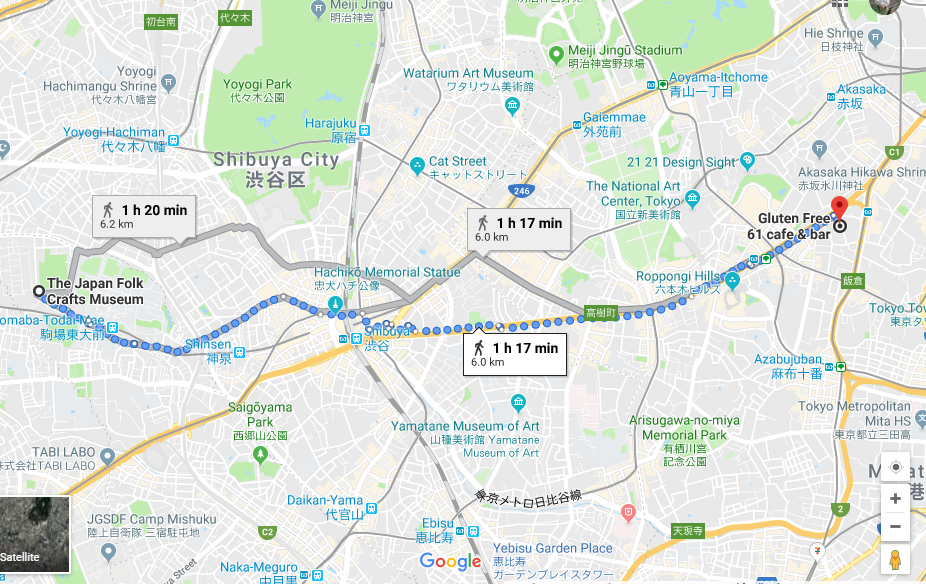

It was late afternoon when I stepped back into my boots and headed out onto the street, a new quest in my sights. In researching one of the attractions listed in my guidebook I’d found out there was a gluten free café in Roppongi which did traditional Japanese food, including okonomiyaki. If you’ve never seen a video of okonomiyaki coming into being, I suggest you leave and find one now so you can understand why I so very much wanted to try it. It’s essentially a meal of everything you can think of piled on top of a pancake base, then drizzled with lashings of okonomiyaki sauce and mayo.

Checking Google maps told me that the cafe was exactly 6km away. Perfect. I would save train fare, earn my dinner, and get to experience that beautiful spring sunset hour as I strolled through real Tokyo neighbourhoods.

That’s what the first part of my walk was– real Tokyo neighbourhoods, full of homes, and real people, and hairdressers, and bakeries, and post offices, and all the other little things that make up a part of a city where people actually live. For 30 minutes I didn’t see a single other foreigner apart from one red-haired guy talking fluently to the woman next to him and giving me the “eww, is that a tourist?” side-eye as I power walked past. The light was beautiful, casting pastel tones across the pale apartment blocks.

And then the peace was shattered by the insanity of Shibuya and my phone maps went crazy so I had to second guess all navigation and I was swept up in a terrible storm of human bodies and mad overpasses and flashing lights. But away from the station that tumbled way to the sleek grey world of Roppongi. At one point I passed a car wash where the combined price tags of the medley of cars in the lot could have bought you a cul-de-sac in London. I felt like I was walking through the senator’s neighbourhood from a dystopian fiction. My walk ran parallel to a huge overpass heaving with traffic in the setting sun. A middle aged man dressed for a fishing trip took photos of a Coca-Cola sign. The officer on duty at a police box I passed eyed me with suspicion.

Gluten Free 61 Cafe is tucked away just of the main road. It was much smaller than I imagined; two little tables and a few seats along the bar, but there’s a reason it’s the number 1 rated place to eat in Roppongi on Trip Advisor. Tokyo is hell for true coeliacs as even regular soy sauce is made with wheat so anywhere that guarantees a safe food experience is a massive draw. I’m not that sensitive, but eating large amounts of wheat, say a bowl of pasta or a slice of cake or a full try of takoyaki, leaves me with three days of joint pain, headaches, fatigue, and super fun digestive problems, so, apart from rare bouts of wild tasty masochism, wheat is not a regular part of my diet.

“こんばんは!” I said to the chef behind the counter.

“Hello!” she replied, and seated me in the corner. I pretended to look at the menu, knowing all along I was here for the everything pancake but not wanting to look too eager. Chef came round to take my order and hand me a survey about being gluten free in Japan.

“えと。。。お好み焼きとビールをください” I said.

“Why are you speaking Japanese?” she asked.

This threw me. As far as I knew, I was in Japan. Attempting to speak Japanese seemed to be the logical option. I can’t remember what I said, probably some mumbled version of “I’m here for a year, so I really should at least make an effort”. It turned out she’d studied in/at Oxford. Perhaps she just missed the English accent. Later when I left the loo I heard her tell her colleague that my command of Japanese was 上手, which is perhaps the overstatement of the century.

The okonomiyaki was a little disappointing, if I’m honest. It mainly just tasted like the sauce and the portion came in much more meagre compared to the huge heaps of cabbage, bacon and egg I’d seen in street food videos. I wish I’d had enough cash to get a few side dishes; every review on Trip Advisor mentions the gyoza. But at least it was the solid end of a hearty quest, and the beer was more than happily received after the long walk.

I took the easy route home. Roppongi Itchome station was nearby, just a short walk through a business grey cavern where suddenly a huge orb in pearlescent plastic over wire and studded with disco balls twirled under colour changing lights. Despite the light burning in the soles of my feet I stood and gawped in wonder at this angelic alien sun for a few moments, then took an obligatory selfie with it and slipped away to the trains. The whole journey home I tried to decipher why I always like the unexpected art encounters more than those I expect. I wish I had an answer, but I don’t.

Hey there! Do you enjoy reading about my travels? Want to show your appreciation?

Help a wanderer out with a donation- paypal.me/RumadeRu

All contributions are very gratefully received!