On my third day in Tokyo, I found a photocopied notice pinned to the wall just outside the hostel elevator. “Do you want to come to a digital art museum?” It said. “I have a spare ticket- hit me up- M. We can take pictures together.” along with an Instagram handle.

“Hey M! Do you still have a ticket going?” I messaged, following it up with my favourite wanky phrase: “I’ll be up on the roof terrace doing yoga until 9.”

It wasn’t long until M popped his head round the door, thankfully not when I was in full fan pose, and we hashed out plans for the day. M decided we should wait until after dark to go to the museum, which he was sure was open until 9pm. We would meet in Odaiba at 7pm. In the mean time, I decided to go and wander Ueno Park.

Thanks to M, I was able to finally realise how terrible and sloppy my tree pose is. Raise your arms, woman!

Back in the day before the Meiji Restoration, Ueno Park was the private grounds surrounding the family temple of the Tokugawa Clan, the shogunate founded by Tokugawa Ieyasu in the Sengoku Era. Today they still house Toshogu Shrine, built in 1626 to honour him. Literally everything I know about the Sengoku era comes from a phone game in which you date famous samurai of the time, including Ieyasu, who is a massive jerkbag in it, so part of the goal of this trip has been to learn more about the actual dude who unified Japan and kick-started two centuries of peace.

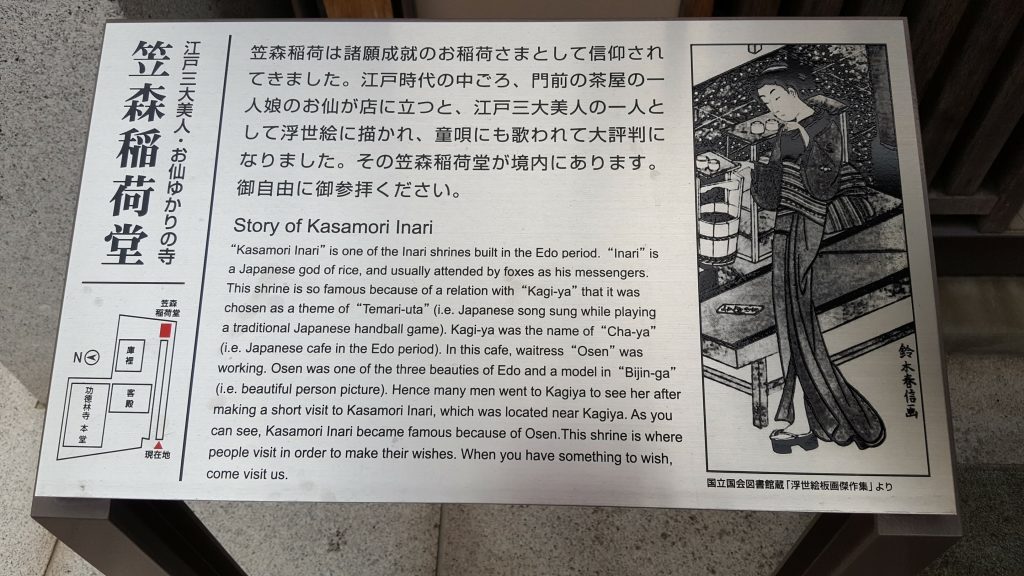

And so I set off across the park, shrine hunting under the not-quite-blooming cherry trees. But here I encountered a common problem: Tokyo has a lot of shrines. I found a line of red tori gates and followed them down a stone path, only to come out at an inari shrine flanked by stone kitsune statues. Was this Toshogu? It seemed fairly modest for anything connected to the Tokugawa. Still, I was here and I didn’t want to offend the kitsune, so I did the purification ritual, put in a coin offering, rang the bell, bowed, clapped, bowed, and bought myself a little fortune from a brightly coloured vending machine.

This one promised me easy childbirth and safe travels as long as I beware of trifles, which is easy because I’ve never been a big fan of the pudding anyway. You can ask my mother.

At the shrine shop, I bought a bell shaped like a frog for the steadily growing collection of talismans that now dangles from my backpack. I have since come to regret this purchase, as with the addition of this bell every step I take announces my coming with all the subtly of a Morris dancer.

Back on the main path, a handy map told me I was headed the right way. The stone street to Toshogu was lined with stalls selling treats, from corn on the cob and sweets like dango, through to a whole grilled squid on a stick for 600¥. As I walked on a stone path that had been trod for more than half a century, I wondered how different, if at all, this scene was from the days when Tokyo had been Edo. As long as there have been cities, there has been street food, and on an even more fundamental level, as long as there has been fire and sticks, humans have been spearing and grilling things.

It’s just what we do.

The stone path opened up into a square in front of the shrine, lined with bronze and stone lanterns. Other tourists milled around snapping pictures in the spring sunshine, as up ahead Toshogu itself gleamed gaudily in black and gold, intricate animal carvings frolicking under the eaves. To the right of the square I noticed what looked like an orange tree in fruit, and, finding it strange in blossom season, went to go take a closer look only to have my eyes drawn to a small memorial in its shade. Inside of a dove shaped lantern, barely visible on this sunny day, a small flame flickered. This is the atomic peace flame, lit from fires that burned after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and from sparks from a roof tile from the aftermath of the bomb on Nagasaki. It’s kept alive and fed as a reminder to all of the dream of a world without nuclear war.

Elsewhere in Ueno Park, you can visit the great bronze face of a Buddha statue, frozen in a disembodied serene smile. The corresponding metal body was melted down to make weapons for the war effort.

It’s a bitter thing to see.

Down by Ueno park’s pond in which a temple sits on a man made island, a market had been set up. I resisted buying a quilted kimono jacket for 200¥on the basis that I might never wear it again, a decision I immediately regretted when the temperature dropped an hour later and I returned to find it gone. By the market, a man coaxed a large and nervous looking monkey to perform in front of a cooing crowd. Across a bridge, lined again with squid sellers and dango dealers, sat the Buddhist temple of Benten-do. At this point perhaps I should mention that I feel like I am running out of ways to describe temples and shrines. Unfortunately for you, dear reader, I am gripped by the need to keep visiting them.

Benten-do is tiny, and was heaving on this Saturday morning. Here I bought my first bundle of incense and made an offering in a brazier off to the right, away from the crowd, hoping that the ignored deity behind it wasn’t the equivalent of the patron saint of murderers and women of ill-repute.

In front of the main temple, stood an easily ignored statue on a plinth. It looked to me like the head of Buddha on the body of a snake, and as I stared at it, an old man approached, and began to touch it, looking fixing me with a stare as he did. Not knowing what to do and feeling slightly uncomfortable, I copied him.

“きれいな” he said, looking right at me and stroking the snakeman’s body harder. “きれいな”

“eh?” I replied, my beginner’s Japanese entirely useless out of context.

“Beautiful!” He grinned and showed a quartet of teeth.

“Oh, uh, ありがとう.” I said. I gave a little bow and left, not having a clue whether he was saying I was beautiful or that the snakeman stroking ceremony was supposed to imbue one with beauty, and annoyed at myself for not picking up on a basic adjective.

On a bench overlooking the boating pond, I ate a sad lunch of a vegan energy bar and a completely joyless tangerine. I’d brought a guide book with me that detailed 42 walks around Tokyo, and it recommended a small museum on the other side of the pond, so I went to check it out.

Shitamachi is well worth a visit. For starters, it’s only 300¥ to get in, and if like me you come at lunchtime when all the other tourists are stuffing their pie holes with tempura and udon, you might be lucky enough to get a one-on-one tour. The museum consists of a replica of a few Edo period buildings downstairs, and a small collection of posters, photos, and other artifacts upstairs. It’s a charming little snapshot of what Tokyo was like before the great earthquake and fire of 1923, and the bombings of WWII.

My guide, a lovely おじさん who spoke amazing English, took me through each little building in great detail, explaining everything from how many people would be sharing a single room, to what the baskets on the ceiling were for, through to what happened to the waste (answers: up to 4; they were for storing precious possessions so they could be easily grabbed in the event of fire, not for storing babies out of the way as I suggested; farmers from outside Tokyo would come and pay landlords for the human fertiliser). I probably spent less than an hour in Shitamachi, but it was a lovely hour nonetheless.

As I left, I noticed a flier for local Taito buses that made loops of the area, including Yanaka Cemetary. I seem to always end up hanging out with dead people when I’m away. Perhaps it’s a hangover from my teenage goth years.

Reasons to visit cemeteries on holiday:

– they’re nearly always quiet, unless it’s Day of the Dead in Mexico City, or similar equivalent

– graveyards are essentially sculpture parks and nearly always filled with interesting statues and old trees

– I am yet to encounter a crowd in one, which is nice if like me you are short and hate being squished up against 1000 stranger’s waists

– You can tell a lot about a people from how they treat their dead

– It shows you a side of a culture you might never have thought of before

– Reminds you of the fragility and temporary nature of your own life and that of everyone you’ve ever known or cared about, which, after all, isn’t what everyone wants to think about on holiday?

The cherry blossoms that run down the main stretch in Yanaka weren’t blooming yet, but it was still a lovely space, rows of neat little grave markers and stone lanterns occasionally punctuated by huge dark slabs. I peered into the Tokugawa plot through the bars of the gate and thought about the cold fact that everyone ends up worm food eventually, shogun or not. Wooden planks called sotoba clacked against each other in the gentle breeze. In the nicest possible way, I felt like someone else was there.

Around Yanaka are a few old style shops that I definitely recommend perusing, especially a used bookshop I found with a small frog statue out front which had a good range of affordable prints and interesting used magazines. There was also another smaller cemetery, where old gnarled trees were propped up with bamboo, and a inari shrine.

Realising the time, I rushed to catch the little bus back to Asakusa, grabbed my coat from the hostel, and leapt on the train to Odaiba to meet M. He was waiting for me just under a ferris wheel.

“So”, he said, sheepishly, “Turns out it was open til 9 yesterday because of something called the equinox? But today it shut at 7.”

The current time was 19:05.

We wandered around Odaiba for a few hours, getting lost in labyrinthine shopping centres, and rejecting Joyopolis among other activities as too expensive, until we found ourselves in front of the Gundam statue.

“Have you watched any Gundam?” he asked me, as I wondered why more cities don’t have giant robot statues.

“Nah. You?”

“I don’t really watch anime.” We stared at the statue for a bit. “I wonder if this is the one that moves, or if that Gundam is”, he said, pointing to another robot on some steps a few metres away.

“That’s Bumblebee from Transformers”, I said, and went to read the sign to my right. My limited Japanese ascertained that there would be a movement and light show in 20 minutes, so we sat on a wall and I ate an onigiri as M told me about his future plans which mainly seemed to involve living with his parents and working at a supermarket indefinitely.

After 20 minutes, a sizeable crowd had gathered. Music began to blare and a video was projected as the robot’s lights changed colour and its face moved a few centimetres, crowd oohed and aahed. I tried not to laugh at the anti-climatic nature of it all. If I’d not known it moved, and just seen it as a big robot statue, I would have come away thinking “oh, neat”, but instead I felt utterly underwhelmed.

Somewhere in that is an important life lesson.

Hey there! Do you enjoy reading about my travels? Want to show your appreciation?

Help a wanderer out with a donation- paypal.me/RumadeRu

All contributions are very gratefully received!